Step aside Ms. Yellen, the US Treasury’s Office of Financial Research has explicitly warned of overvalued and overleveraged US stock markets!

In her recent report to the US Congress, Fed Chair Janet Yellen issued sanitized warnings in some areas of the Financial sector.

On the other hand, a recent report from the US Treasury’s Office of Financial Research admonishes on heightened risks of financial instability from current conditions in details!

From OFR’s Ted Berg’s QuickSilver Markets (bold mine footnotes omitted)

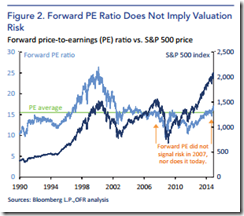

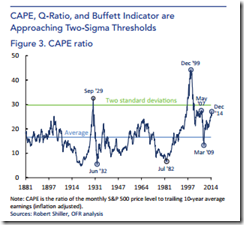

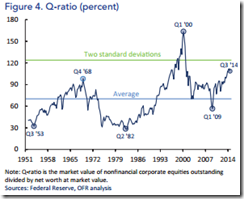

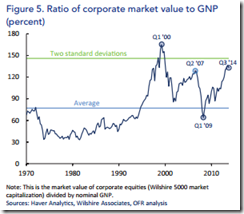

Some Valuation Metrics Are Nearing Extreme HighsToday, equity valuations appear reasonable based on commonly used metrics such as the forward PE, price-to-book, and priceto-cash flow ratios. But these metrics do not tell the whole story.Take, for example, the simple PE ratio, which is a quick and easy way to evaluate stock prices (see Figure 2). It’s a convention that emerged mostly as a result of “tradition and convenience rather than logic,” according to Robert Shiller. Forward PE ratios are potentially misleading for several reasons. First, forward one-year earnings are derived from equity analyst projections, which tend to have an upward bias. During boom periods, analysts often project high levels of earnings far into the future. As a result, forward PE ratios often appear cheap. Second, one-year earnings are highly volatile and may not necessarily reflect a company’s sustainable earnings capacity. Third, profit margins typically revert toward a longer-term average over a business cycle. The risk of mean reversion is particularly relevant today, because profit margins are at historic highs and analysts forecast this trend to continue.Other fundamental valuation metrics tell a different story than the forward PE. This brief focuses on a few — the CAPE ratio, the Q-ratio, and the Buffett Indicator — that are approaching two-standard deviation (two-sigma) thresholds.Why is two-sigma relevant? Valuations approached or surpassed two-sigma in each major stock market bubble of the past century. And the bursting of asset bubbles has at times had important implications for financial stability. The two-sigma threshold is useful for identifying these extreme valuation outliers. Assuming a normal distribution in a time series, two-sigma events should occur once every 40-plus years; in equity markets, they occur more frequently due to fat-tail distributions.

In the following, I post the OFR’s comments on the CAPE ratio, the Q-ratio, and the Buffett Indicator with the exclusion of their methodology and their caveats.

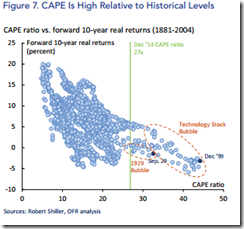

CAPE Ratio.The historical CAPE average based on a 133-year data series is approximately 17 times, and its two-standard-deviation upper band is 30 times. The highest market peaks (1929, 1999, and 2007) either surpassed or approached this two-sigma level (1999 exceeded four sigma). Each of these peaks was followed by a sharp decline in stock prices and adverse consequences for the real economy. At the end of 2014, the CAPE ratio (27 times) was in the 94th percentile of historical observations and was approaching its two-sigma threshold.Q-Ratio.The Q-ratio, defined here as the market value of nonfinancial corporate equities outstanding divided by net worth, suggests a similar message of equity valuations approaching critical levels (see Figure 4).7 Instead of using a traditional accounting-based (historical cost) measure of net worth, the Q-ratio incorporates market value and replacement cost estimates. The Q-ratio also includes a much broader universe of nonfinancial companies (private and public) than CAPE.Buffett Indicator.The ratio of corporate market value to gross national product (GNP) is at its highest level since 2000 and approaching the two-sigma threshold (see Figure 5). This indicator is informally referred to as the Buffett Indicator, because it is reportedly Berkshire Hathaway Chairman Warren Buffett’s preferred measure to assess overall market valuation. Historically, this indicator’s message is consistent with CAPE, particularly in identifying periods of extreme valuation before the Great Recession and the 1990s technology stock bubble.The earnings mean reversion.

High valuations equals High risk and lower returns

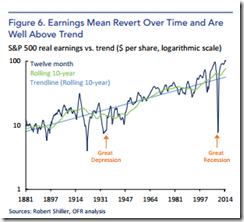

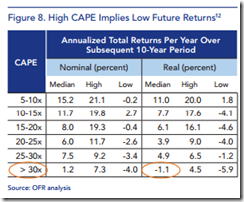

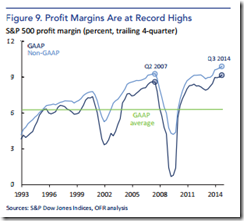

Evaluating the Possibility of a Market CorrectionHistory shows a clear relationship between the CAPE ratio and forward 10-year compounded annual real returns (see Figure 7).11 High valuations today imply lower future returns. However, none of these valuation metrics — the CAPE ratio, the Q-ratio, or the Buffett Indicator — predicts the timing of inflection points, and markets may remain undervalued or overvalued for very long periods. But we can use these metrics as barometers to gauge when valuations are reaching excessively high or low levels. The timing of market shocks is difficult, if not impossible, to identify in advance, let alone quantify — a shock, by definition, is unexpected. When assessing asset valuation it is important to make a distinction between risk and uncertainty. Risk may be quantified and described in probabilistic terms, and analysts can factor this into their valuation models. However, uncertainty is hard to quantify because it refers to future events that cannot be fully understood or quantified. Today’s high stock valuations imply that investors underestimate the potential for uncertain events to occur.Figure 8 shows the relationship between valuation and future returns more explicitly.Historically, the highest returns follow periods of low valuations (CAPE < 10) and the lowest returns Figure 6. Earnings Mean Revert Over Time and Are Well Above Trend Figure 7. CAPE Is High Relative to Historical Levels 1 10 100 1881 1897 1914 1931 1947 1964 1981 1997 2014 S&P 500 real earnings vs. trend ($ per share, logarithmic scale) Twelve month Rolling 10-year Sources: Robert Shiller, OFR analysis Trendline (Rolling 10-year) Great Recession Great Depression OFR Brief Series March 2015 | Page 5 follow periods of high valuations (CAPE > 30). When setting expectations for future returns, CAPE appears most relevant at these extreme lows (expect above-average future returns) and highs (expect below-average future returns). In fact, real returns were negative, as shown in Figure 8, when CAPE exceeded the two-sigma threshold. Similar conclusions may be drawn from other metrics, such as the Q-ratio and Buffett Indicator, but the historical time series associated with them are shorter.To be clear, extreme valuations (2-sigma) are only one characteristic of a potential bubble. Valuation in isolation is not necessarily sufficient to trigger a downturn, let alone pose risks to financial stability. Other factors are relevant for analyzing market cycles — most important, corporate earnings.Robust growth in corporate earnings is the primary driver behind the stock market’s gains over the past several years. But sales growth has been much more modest. Since the cyclical low in 2009, earnings have increased at a double-digit annual growth rate while sales have increased at a more modest mid single-digit rate. The higher trend growth in earnings versus sales is due to rising profit margins. S&P 500 profit margins reached a record 9.2 percent (trailing 4-quarter, GAAP) in the third quarter of 2014 (see Figure 9), well above the historical average of 6.3 percent.Broader measures of corporate profitability (before and after tax) tell a similar story (see Figure 10). The Bureau of Economic Analysis corporate profit data series covers approximately 9,000 companies, public and private, so it is a much broader measure than S&P 500 profits.To date, record high margins are in part supported by favorable secular trends: a greater proportion of high margin sectors in the S&P 500 composite, lower corporate effective tax rates due to a higher mix of foreign profits, and productivity improvements such as automation and supply chain enhancements. The lower margin, capital-intensive sectors that dominated the market index in earlier decades have given way to more profitable and less capital-intensive sectors due to the computing revolution (early 1980s) and the gradual transition to a services-driven economy. Since the 1970s, lower margin, capital-intensive sectors (industrials, materials, and energy) have fallen from 39 to 22 percent of S&P 500 market capitalization, while higher margin sectors (technology, financials, and health care) have risen from 23 to 50 percent.Other favorable cyclical factors have also helped to boost profitability, including low interest rates, low labor costs, cost-cutting initiatives, and positive operating leverage (high fixed costs relative to variable costs). However, many of these are not sustainable. Current historically low interest rates will eventually rise. Labor costs will increase as unemployment decreases, and cost-cutting initiatives, such as underinvestment in research and development and capital spending (key sources of future revenue growth), cannot continue indefinitely. Finally, positive operating leverage works in reverse when the sales cycle turns.Of course, the current cycle could continue as long as revenue growth offsets these margin pressures.Taking a longer-term view, beyond a single cycle, competitive market forces are another key factor that limits future margin expansion. Profitable industries eventually attract new capital and new competitors, ultimately reducing margins over time in mature industries. This is particularly true in a highly competitive global economy.Mean reversion in margins has important implications for equity valuations. The current forward PE ratio appears reasonable only if record margins are sustained. During business cycle peaks, when margins are high, investors often fail to factor margin mean reversion into earnings estimates and then adjust forward PEs lower to compensate for this risk.

I have always emphasized here that there are limits to anything including earnings growth. This is most especially relevant when zero bound rates induces a frontloading of growth through leverage.

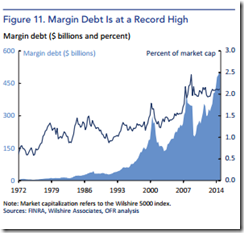

Leverage.Leverage can magnify the impact of asset price movements. Leverage achieved through stock margin borrowing played an important role in inflating stock prices in the 1929 stock market bubble and to a lesser extent in the late 1990s technology stock bubble. Margin debt, according to the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority, reached a record $500 billion at the end of the third quarter of 2014, representing just over 2 percent of overall market capitalization. Although this percentage is below the peak in 2008, it is higher than historical levels (see Figure 11). The percentage does not appear alarmingly high, but forced sales of equities by large leveraged investors at the margin could be a catalyst that sparks a larger selloff. Other forms of leverage, such as securities lending and synthetic leverage achieved through derivatives, may also present risks.Another component of leverage in the system is the financing activities of corporations. Today, high profits have made corporate balance sheets generally quite healthy. As of the third quarter of 2014, U.S. nonfinancial corporations held a near-record $1.8 trillion in liquid assets (cash and financial assets readily convertible to cash). However, corporations also have racked up a record amount of debt since the last crisis. U.S. nonfinancial corporate debt outstanding has risen to $7.4 trillion, up from $5.7 trillion in 2006. Proceeds from debt offerings have largely been used for stock buybacks, dividend increases, and mergers and acquisitions. Although this financial engineering has contributed to higher stock prices in the short run, it detracts from opportunities to invest capital to support longer-term organic growth. Credit conditions remain favorable today because of the positive trend in earnings, but once the cycle turns from expansion to downturn, the buildup of past excesses will eventually lead to future defaults and losses. If interest rates suddenly increase, then financial engineering activities will subside, removing a key catalyst of higher stock prices

Zero bound rates signify as subsidy to interest rate sensitive sectors of the economy and markets, take these away, then there will be withdrawal syndroms.

ConclusionMarkets can change rapidly and unpredictably. When these changes occur they are sharpest and most damaging when asset valuations are at extreme highs. High valuations have important implications for expected investment returns and, potentially, for financial stability.Today’s market environment is different in many ways from the period preceding the Great Recession, because regulators and market participants have made adjustments to enhance financial stability since the financial crisis. In that time, stock returns have been exceptional and market volatility generally subdued. Today, many market strategists see the bull market extending throughout 2015.However, quicksilver markets can turn from tranquil to turbulent in short order. It is worth noting that in 2006 volatility was low and companies were generating record profit margins, until the business cycle came to an abrupt halt due to events that many people had not anticipated. Although investor appetite for equities may remain robust in the near term, because of positive equity fundamentals and low yields in other asset classes, history shows high valuations carry inherent risk.Based on the preliminary analysis presented here, the financial stability implications of a market correction could be moderate due to limited liquidity transformation in the equity market. However, potential financial stability risks arising from leverage, compressed pricing of risk, interconnectedness, and complexity deserve further attention and analysis.

You have been warned.

No comments:

Post a Comment